Note: this entry is part of a series of posts which explain some of the technical features of my lab notebook.

Archival preservation of digital scholarly content is an important challenge throughout the research community. As the notebook is the permanent record of my regular scholarly endeavors, this provides the opportunity to experiment with tools and techniques for digital archiving while also better preserving the notebook. In the experimental spirit that drives all my exploration here, I am testing several ways to accomplish this. In so doing, I learn which approaches are easiest to implement, to use, and gather feedback from, while also hedging my bets in the event that any given strategy should fail.

Archiving digital content involves two fundamental challenges that can be difficult to satisfy simultaneously: providing a robust backup copy of the content, and providing a consistent location (such as a URL) where the content can be retrieved.

A custom domain

The simplest archival measure employed in the notebook comes from hosting through my own domain, carlboettiger.info rather than an external server. By controlling the domain structure myself, I am not tied to a University server that can be altered by an IT department without my knowledge, thereby breaking my links. When I choose to move platforms, as I did in migrating from Wordpress to Jekyll, I could ensure that links would be appropriately mapped. This was not the case when I started my open notebook on the OpenWetWare platform, since links are all mapped to the openwetware.org domain which I obviously cannot control, even though I could at least migrate my content. HTML redirects make sure links still resolve when I change structure (e.g. carlboettiger.info/archives/211). I don’t have to worry about moving my domain when I change institutions, and can seamlessly migrate to a different server or DNS provider to get better rates or uptime performance.

Of course these advantages are also the greatest weaknesses of this approach – they all depend entirely on me. I could make or forget to make any number of changes that could cause this all to break. Time has shown that even the best-intentioned researchers are not the best curators of there own data, and no doubt I am no exception. How can the content and its identifying addresses outlive me or my interest in it?

PURLs: preserving identifiers

PURLs, or Persistent Uniform Resource Locators, provide a DOI-like mechanism for addressing the challenge of link-rot. As Geoffrey Bilder eloquently argues, the technological solution is quite simple, the real challenge lies on the social side of the implementation – a social contract that promises content providers will maintain their identifiers if they want to continue to receive identifiers. Though users must register to be able to create PURLs, PURL does not provide such enforcement.

The PURLs solution is a bit more web-native solution than DOIs, in being more democratic, using a URL structure, and being built upon widely distributed servers and open-source web technology. Not surprisingly, other web-native systems such as most of the major semantic web ontology providers rely on PURLs, e.g. Dublin Core uses purl.org/dc/terms/. The PURL FAQ provides a great overview.

Implementing PURLs for the notebook was very straight-forward. After registering as a user at purl.org I applied for my own top-level domain: cboettig, which I then mapped to my current domain, carlboettiger.info By enabling partial redirects, each page on my site will also be resolved using this top-level domain followed by my existing page structure. Following my existing structure is not necessary – I could map each page to an arbitrary path in my domain, but would have to enter these somewhat manually. While the partial redirect is simpler to implement, it does require that I maintain the rest of the link structure.

In this way, purl.org/cboettig/lab-notebook.html now resolves to carlboettiger.info/lab-notebook.html. Likewise, each page in the notebook can be similarly resolved from the purl.org domain instead of my personal carlboettiger.info domain. Should I ever somehow lose control of carlboettiger.info, I could re-assign my PURL to redirect to my new domain URL. This provides DOI-like technology of permanent identifiers for every page in the notebook.

GitHub: preserving content and versions

Committing content to an external repository is the recommended way to avoid link-rot from the user errors and website changes that so frequently plague self-archiving of scholarly content. Keeping multiple copies of content in geographically distinct locations is the time-honored approach of digital archiving. Git and GitHub make this easy. Not only does this mean that a backup copy is publicly available and forkable online, but it is also easy to clone copies on each of the machines I work on and rely on git to keep them in sync. Should Github disappear, a little git remote add and everything will be effortlessly deployed with complete history elsewhere.

The notebook has two Github repositories: the “source-code” consisting of plain-text (markdown) content and Jekyll-based templates on labnotebook, and a second for the rendered HTML cboettig.github.com (which also now hosts the website).

While a custom domain and PURLs provide persistent locators for the content, distributed copies on Git help archive the content itself. Should my domain vanish or Github disappear, copies of the content, complete with version history, would remain distributed across various machines with a copy of the repository. Links to Github would break in that process, unless we had remapped all links from the notebook to Github using PURLs.

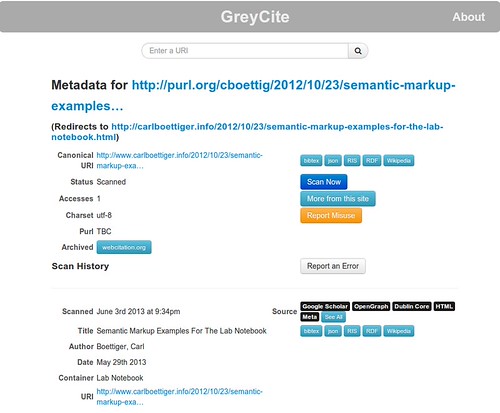

Greycite: Programmatic access and indexing of metadata

I think of good metadata as the third leg to proper digital archiving, in addition to permanent identifiers and backup of content. We want to be able to point a tool at the permanent identifier / URL of an entry and extract reliable information on the author, time published and last modified, title, author, key words, etc. that might be useful in citing or categorizing the content. Providing this information is really the subject of adding Semantic metadata to the site, and is covered in another entry in this series. Meanwhile, the Greycite tool and it’s API are an excellent way to extract this metadata into a variety of useful formats, working much the same way that CrossRef’s tool does using DOIs. Here is an example query

Robust archiving with figshare

Depositing a copy of the notebook on figshare is one of the most robust archival solutions of which I am currently aware. Not so much because it has the coveted DOI solution to the permanent identifier problem but because it has the promise of CLOCKSS archiving, should anything ever happen to figshare.

Nevertheless, it raises several challenges. The native home for the content is as rendered HTML at my domain, not as raw HTML on an archive completely unassociated with that domain, difficult to view, and divorced from my usual workflow, unlike my usual publishing source-code to Github and website to my domain. It also raises questions of just what to archive and when. I discuss some of these strengths and challenges as a separate post, archiving the lab notebook on figshare: advantages and challenges.

Conclusions

Digital archiving is a challenging problem that is not completely addressed by any one of these approaches. In the end, robust archiving will be best left in the hands of its experts. Unfortunately, the best examples currently available (such as CLOCKSS, national libraries, etc.) will not archive a researcher’s web page directly. The solutions explored here are not perfect, but they are free and simple to implement. I’d love to hear what others think.