Another unexpected gem from keeping an online notebook: Empirical evidence for the expected escape time problem! Getting to that in a moment….

After Marc pointed out to me that there is a clever analytic demonstration to back my claims about realized exit times being fast (posted earlier in my notebook under the title, a clever derivation of realized escape times, I’ve enjoyed a bit of a tangent in understanding this result that has long since been worked out by mathematicians but appears to be periodically rediscovered in ecological and evolutionary work in the most delightful ways.

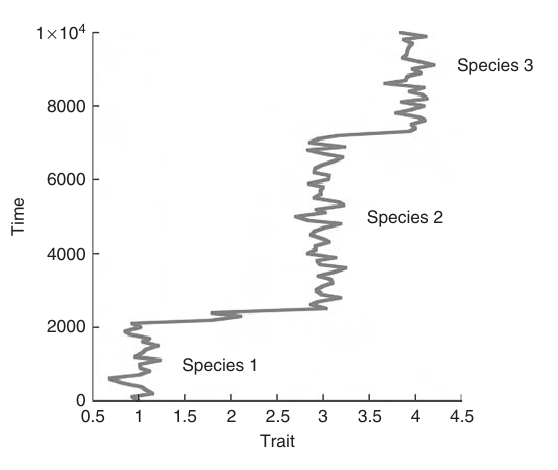

For instance, Lande (1985) shows how this result can explain a pattern of punctuated equilibrium, such as sudden rapid jumps such as illustrated below in a simulation example from Freidlin et. al. (1998), need not result from some external process but are in fact the most likely trajectories to be seen in a purely stochastic transition.

Ludwig (1975) considered this result in a more ecological context, addressing a variety of questions about persistence and coexistence that are naturally represented as hitting time problems as well. Note that the this result is interesting precisely in its contrast from the more familiar hitting time problems in that we focus on the time the realized trajectory actually takes to exit, rather than the waiting time until that exit occurs (e.g. the frequency of the transtions shown in the figure above).

These examples appear to be rediscoveries of particular cases that result more generally from the large deviation theory of Fiedlin and Wentzell, which states that the most likely path can be found by minimizing a variation equation (Hamiltonian, analgous to the minimizing action along paths in classical mechanics or the optimization under constraint of Jacobi-Bellman). For a system of discrete steps (e.g. births and deaths) in one dimension this is particularly trivial: the most likely path is the monotonic one (this should be easy to see by considering the likelihood of \(N\) death events occuring in sequence vs that of \(N-1\) death events interrupted by 1 birth and followed by 2 deaths.)

Empirical demonstrations?

Then an email to me earlier this week pointed out that perhaps an example of the phenomenon I discussed there had been demonstrated in Drake & Griffen (2009) :

A testable, counter-intuitive prediction of stochastic population theory is that, on average, for any interior interval of the domain of biologically attainable population sizes, the expected duration of increase equals the expected duration of decline. Here we report the first empirical tests of this hypothesis.

I do feel that this is an overstatement of the stochastic theory as I understand it – these times should only scale in a similar way, but can differ by an arbitrary coefficient. Indeed it is often the goal of the deviation theory analysis to determine this coefficent, see Faure & Schreiber (2011) . The authors seem quite concerned that theory they refer to applies to continuously valued diffusion processes alone, whereas I’m quite certain the more general results of the deviation theory hold just as well in discrete systems. (Perhaps this explains why they do not confirm this prediction in some subset of the data). Nevertheless, the context is the same as we consider – comparing the return time to a stable point from some small population size with the time required to decline from that point to a small size, as clearly indicated in Figure 1 of the manuscript.

Commendably, the authors make the data and code available (as an R script and .Rdata file). (According to the manuscript, this data is at https://dragonfly.ecology.uga.edu/drakelab/data.html, but in an example of link rot and the risk of independent archiving the lab prefers daphnia to dragonfly, and the data can now be found: https://daphnia.ecology.uga.edu/drakelab/datapage.html). These data draw on work from earlier experiments that provide some of the nicest sources of time series leading up to stochastic extinctions. Unfortunately it appears that only the duration of growth and extinction times for the replicates are shown in the data provided for this paper, I don’t see the actual timeseries themselves (which would be interesting to look at more closely).

References

- John M. Drake, Blaine D. Griffen, (2009) Speed of Expansion And Extinction in Experimental Populations. Ecology Letters 12 772-778 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01325.x

- Mark Freidlin, Alexander Wentzell, (1998) {Random Perturbations of Dynamical Systems (Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften)}. 429-NA https://www.amazon.com/Perturbations-Dynamical-Grundlehren-mathematischen-Wissenschaften/dp/0387983627

- R Lande, (1985) Expected time for random genetic drift of a population between stable phenotypic states. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences https://www.pnas.org/content/82/22/7641.short

- Mathieu Faure, Sebastian Schreiber, (2011) Quasi-Stationary distributions for Randomly perturbed dynamical systems. arXiv.org https://arxiv.org/abs/1101.3420