Pagel’s \(\lambda\) (lambda), introduced in Pagel 1999 as a potential measure of “phylogenetic signal,” the extent to which correlations in traits reflect their shared evolutionary history (as approximated by Brownian motion).

Numerous critiques and ready alternatives have not appeared to decrease it’s popularity. There are many issues with the statistic, some of which I attempt to summarise below.

The \(\lambda\) statistic is defined by the Brownian motion model together with a transformation of the branch lengths: multiply all internal branches by \(\lambda\). The motivation for the definition is obvious: \(\lambda = 1\) the tree is unchanged and the model equivalent to Brownian motion, while for \(\lambda = 0\) the tree becomes a star phylogeny and the model is equivalent to completely independent random walks. \(0 < \lambda < 1\) provides an intermediate range where the correlations are weaker than expected.

Problem 1: It is biological nonsense to treat tips different from other edges.

All other problems arise from this. While it is okay that a statistic does not have a corresponding evolutionary model, being part of an explicit model might have helped avoid this sillyness. Technically \(\lambda\) is a model, but one that treats evolution along “tips” as special, as if evolution should follow completely different rules for a species alive today relative to it’s former evolutionary history. Sounds almost creationist.

Problem 2: The statistic doesn’t measure what is says it measures.

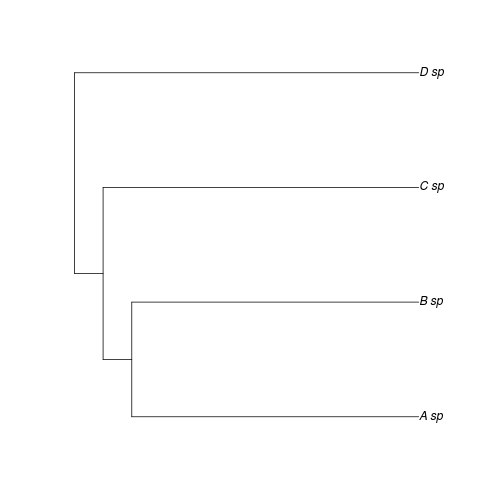

To demonstrate this, we can consider two cases in which phylogeny has the identical effect of explaining trait correlations, and yet have very different lambdas. Consider that Researcher 1 examines the phylogeny in Figure 1 and estimates very little phylogenetic signal, \(\lambda = 0.1\).

library(ape)

cat("(((A_sp:10,B_sp:10):1,C_sp:11):1,D_sp:12);", file = "ex.tre", sep = "\n")

ex <- read.tree("ex.tre")

plot(ex)

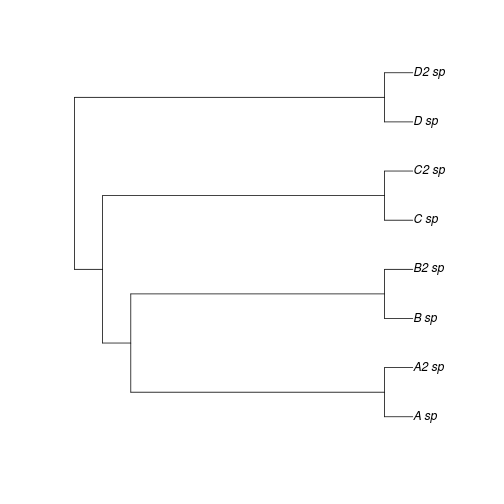

Now Researcher 2 discovers closely related sister species of some of the taxa originally studied, as in Figure 2.

cat("((((A_sp:1, A2_sp:1):9,(B_sp:1, B2_sp:1):9):1,(C_sp:1, C2_sp:1):10):1,(D_sp:1, D2_sp:1):11);",

file = "ex2.tre", sep = "\n")

ex2 <- read.tree("ex2.tre")

plot(ex2)

There traits of sister taxa are very similar (indeed let us assume the sister species are hard to distinguish morphologically - perhaps why they were overlooked by Researcher 1). The OU or BM model estimates made by researcher 1 will closely agree with with those of Researcher 1, since the sister taxa have quite similar traits. Yet the \(\lambda\) estimates differs greatly – all of a sudden the phylogenetic signal must be quite high!

And yet the underlying evolutionary process by which we have simulated the data has been unchanged! The difference arises because what formerly appeared as long tips have become short tips. How do we intepret a metric that depends so heavily on whether or not all sister species are present in the data? As noted, this problem does not impact other phylogenetic comparative methods to nearly the same extent.

Problem 3 The statistic has no notion of timescale or depth in the phylogeny.

In \(\lambda\) (and other definitions such as Blomberg’s K), phylogenetic signal is an all-or-nothing proposition. If we find that really recently diverged species that happen to resemble each-other, while species that have diverged for longer than, say, a couple million years show no correlation – is this phylogenetic signal or not? This ‘extinction’ of phylogenetic signal as we go far enough back in time seems like a biologically reasonable concept that is perfectly well expressed in the \(\alpha\) parameter of the OU model, but is lost in the consideration of \(\lambda\). If folks really want to estimate a continuous quantity to measure phylogenetic signal, I suggest \(\alpha\) is a far more meaningful number (note that it has units! (1/time or 1/branch length)).

Consider the returning force alpha in the OU model (i.e. stabilizing selection). When alpha is near zero, the model is essentially Brownian, (i.e. ‘strong phylogenetic signal,’ where more recently diverged species are more similar on average than distantly related ones). When alpha is very large, traits reflect the selective constraint of the environment rather than their history, and so recently diverged species are no more or less likely to be similar than distant ones (provided all species in question are under the same OU model / same selection strength for the trait in question). The size of alpha gives the timescale over which ‘phylogenetic signal’ is lost (in units of the branch length). Two very recently diverged sister-taxa may thus show some phylogenetic correlation because their divergence time is of order 1/alpha, while those with longer divergence times act phylogeneticly independent, such as in our Figure 2 above. I find this an imperfect but reasonable meaning of phylogenetic signal.

If we restrict \(\lambda\) to be strictly 1 or 0 these problems are alliviated, though then it is unnessary to define the statistic as such as we may instead consider a star tree (sometimes called the “white noise” model of evolution).

other such statistics

Pagel’s \(\delta\) is a transformation on node depth, which is again problematic as there is no meaningfully consistent way to describe what is a node (think about deep speciation events with no present day ancestor.) I believe \(\kappa\) would also be problematic to interpret as it is a nonlinear transform of branch length – raises branch length to a power – and thus would have a rather different effect depending on the units in which branch length were measured. (For instance, consider the case where the tree is scaled to length unity, so all branch lengths are less than one and thus become shorter with large exponents, vs one in which lengths are all larger than one). Fortunately these statistics are far less popular than \(\lambda\).